I will start with the background of Inline Assembler as it is a way for C/C++ language and Assembler language to co-exist in the same program.

Background:

Inline Assembler Language:

Allows the use of Assembler language within a C language program to prevent certain values from changing during the compiling stage of the program. This will allow the programmer to interact with the memory using the asm code and set the memory location with specific code. This is useful when using the same values over and over again without having to recreate the values. It is like using a function or header file for C programming language.

Syntax:

asm(...);

or

__asm__(...); //This uses double underscores

You can force the compiler not to move the register values of specified registers using the constraint “volatile”.

Ex.1 Volatile Constraint asm:

asm volatile (…);

or

__asm__ __volatile__ (…);

The line of assembly code is placed in between the parenthesis.

The code can have:

1) Assembler Template(Mandatory)

2) Output Operands(Optional)

3) Input Operands(Optional)

4) Clobbers(Optional)

Assembler Template

The assembler template will be the code written in Assembler language.

For example(Aarch64 system):

"mov %1, %0; inc %0"

For example(X86_64 system):

"mov %r8, %%rax; inc %%rax"

Note: the X86_64 system must use a double percent sign to indicate a percent sign. (This is similar to regular expressions in coding where double of a certain character means an escape character.)

Inline Assembler language has a syntax/ format of code.

The following are allowed:

asm("mov %1, %0\ninc%0);

__asm__("mov %1,%0\ninc %0);

__asm__ ("mov %1,%0\n" "inc %0");

__asm__ ("mov %1,%0\n\t"

"inc $0");

The following are not allowed:

asm("mov %1,%0

inc %0"); //There is not ending double quotes on the first line

__asm__("mov %1,%\n","inc %0"); //Cannot place a comma in between the strings

Output and Input Operands

The output operands are the second parameter in Inline Assembler. The input operands are the third parameter in Inline Assembler

Ex.1 Where the output and input operands are:

asm("...";

: "=r" //Output Operand

: "r" //Input Operand

:

);

Constraints

Assembler language is using register values instead of the traditional variables. The output or input operand is not always needed.

There are however some constraints, such as: "r" - any general purpose register is permitted "0-9" - same name register should be used as operand. (For example: register "1" is used so the operand should also be "1". This is to avoid confusion of where the register and operand are.) "i" - an immediate integer value is permitted "F" - an immediate floating-point value is permitted

Other constraints are platform-specific like SIMD or floating-point registers so refer to a reference manual. Here is one for GNU Assembler: http://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc-4.8.2/gcc/Extended-Asm.html

Output Operands

There are certain constraints for output registers. Here are some example:

"=" (output-only register) previous contents are replaced with output value only. (Does not preclude use as an input register, meaning it is not permanently set/ lock the register for output only.) "+" (input and output register) used as both input and output register to input into the asm code and output from the asm code. "&" (early clobber register) This register can be overwritten before input is processed. It is best not to use this register as an input register. "%" (commutable/interchangeable) Besides platform specific constraints, this percent sign with a matching operand and the following operand are both interchangeable for optimization.

Here are some examples written in C language and Inline Assembler language:

Ex.1 Set values to two registers(x86_64):

int x=10,y; __asm__ (mov %1,%0" : "=r"(y) //output is moved to "y" and the corresponding assembly register is register "0". : "r"(x) //input of "x" is placed in a general purpose register. Assembly Register "1" is used here. : );

Ex.2 Make the second operand as a read/write register(x86_64):

int x=10, y;

__asm__ ("mov %1, %0"

: "+r"(y) // + makes the register a read/write register

: "0"(x) // Sets Output the same as Assembly Register 0 (%0).

:

);

Ex.3 Naming/ assigning alias to registers(x86_64):

int x=10, y;

__asm__ ("mov %[in],%[out]"

: [out]"=r"(y) //This Assembly Register has an alias/name of "out".

: [in]"r"(x) //This Assembly Register has an alias/name of "in".

:

);

Specific Register Width(Aarch64 system):

A 32-bit width register uses contraint/ modifier of “w”. For example: C language Register 0 (%0) of Assembler language Register (x28) needs to be converted into a 32-bit wide register. Access a 32-bit wide register by using “%w0”.

Constraining Operands

Constraining operands to a specific register is useful when it is used as an input for a function or syscall. This will avoid the need to rewrite the operand into another register or use more system resources to handle a function.

Ex.1 Register a name/alias to a register (In C language):

register int *foo asm ("a5");

Ex.2 Register a specific register to an operand (Aarch64 system, In C language and Assembler Language):

int x=10;

register int y asm(“r15”);

asm("mov %1,%0; inc r15;"

: "=r"(y)

: "r"(x) // Assembler Register r15

:

);

Note: The C language already assigns “y” to Assembler Register “r15”.

register int y asm("r15");

The Assembler instruction then performs the “mov” command and then the “inc” command to Assembler Register “r15”. Constraiting the register in C language will stop the Assembler language from incrementing before moving the operands. (Sometimes the compiler will optimize for incrementing before moving the operands)

i386 Register Constraint

On i386 systems, registers may be selected using the “a” “b” “c” or “d” names instead of the “r” register constraint.

Cobbler(Overwrites registers)

This is the fourth parameter that is optional but is used when registers or memory regions are being overwritten.

Ex.1 Clobber in x86_64:

asm("..."

: "=r"(out)

: "r"(in)

: "rax", "rbx", "rsi" // values in Assembler Register rax, rbx, rsi will be clobbered

);

Memory

The constraint “memory” should be added as a string to the clobber list when an asm code alters the memory. This forces the compiler to ignore/ mistrust the memory values before the asm code is executed. This is a way to make certain that a value in memory before the asm code is still the same value after the asm code is executed. It is recommended to use the volatile constraint with the memory clobber constraint.

Testing/ Experimenting:

Test 1:

The actual testing will now begin. The testing is done on an Aarch64 Fedora Linux OS system with a Cortex-A57 octa-core CPU.

SQDMULH Instruction

“Signed Saturating Doubling Multiply return High Half”. Basically multiplying two 16-bit signed values will result in a 32-bit value. In a fixed-point 32-bit result, there are 16-bits high values and 16-bits low values. The instruction then takes only the high half of the 32-bits discarding the lower 16-bits.

There are a couple of files that will be used. vol.h, vol_simd.c, Makefile. These files were provided to me by Chris Tyler (Chris Tyler), a Seneca college professor.

vol.h:

#define SAMPLES 500000

vol_simd.c:

// vol_simd.c :: volume scaling in C using AArch64 SIMD

// Chris Tyler 2017.11.29-2018.02.20

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include "vol.h"

int main() {

int16_t* in; // input array

int16_t* limit; // end of input array

int16_t* out; // output array

// these variables will be used in our assembler code, so we're going

// to hand-allocate which register they are placed in

// Q: what is an alternate approach?

register int16_t* in_cursor asm("r20"); // input cursor

register int16_t* out_cursor asm("r21"); // output cursor

register int16_t vol_int asm("r22"); // volume as int16_t

int x; // array interator

int ttl; // array total

in=(int16_t*) calloc(SAMPLES, sizeof(int16_t));

out=(int16_t*) calloc(SAMPLES, sizeof(int16_t));

srand(-1);

printf("Generating sample data.\n");

for (x = 0; x < SAMPLES; x++) {

in[x] = (rand()%65536)-32768;

}

// --------------------------------------------------------------------

in_cursor = in;

out_cursor = out;

limit = in + SAMPLES ;

// set vol_int to fixed-point representation of 0.75

// Q: should we use 32767 or 32768 in next line? why?

vol_int = (int16_t) (0.75 * 32767.0);

printf("Scaling samples.\n");

// Q: what does it mean to "duplicate" values in the next line?

__asm__ ("dup v1.8h,%w0"::"r"(vol_int)); // duplicate vol_int into v1.8h

while ( in_cursor < limit ) {

__asm__ (

"ldr q0, [%[in]],#16 \n\t"

// load eight samples into q0 (v0.8h)

// from in_cursor, and post-increment

// in_cursor by 16 bytes

"sqdmulh v0.8h, v0.8h, v1.8h \n\t"

// multiply each lane in v0 by v1*2

// saturate results

// store upper 16 bits of results into v0

"str q0, [%[out]],#16 \n\t"

// store eight samples to out_cursor

// post-increment out_cursor by 16 bytes

// Q: what happens if we remove the following

// two lines? Why?

: [in]"+r"(in_cursor)

: "0"(in_cursor),[out]"r"(out_cursor)

);

}

// --------------------------------------------------------------------

printf("Summing samples.\n");

for (x = 0; x < SAMPLES; x++) {

ttl=(ttl+out[x])%1000;

}

// Q: are the results usable? are they correct?

printf("Result: %d\n", ttl);

return 0;

}

Makefile:

BINARIES = vol_simd

CCOPTS = -g -O3

all: ${BINARIES}

vol_simd: vol_simd.c vol.h

gcc ${CCOPTS} vol_simd.c -o vol_simd

test: vol_simd

bash -c "time ./vol_simd"

gdb: vol_simd

gdb vol_simd

clean:

rm ${BINARIES} || true

These are the testing requirements for the sampling program:

1) Copy, build and verify the operations of the program 2) Test the performance results 3) Change the sampling size(in vol.h) to produce a measurable runtime 4) Adjust the code to have comparable results. (number of samples, 1 array vs 2 arrays, etc.) 5) Answer the questions in the source code (in vol_simd.c) 1) Copy, Build, Verify Operations I start with by building the program:

The following is the command to build the program:

gcc -g -O3 vol_simd.c -o vol_simd

Similarly, I could run this command since the Makefile is configured with the vol_simd settings:

make vol_simd

Next I ran this command to run the program:

./vol_simd

The result:

Generating sample data. Scaling samples. Summing samples. Result: -574

Next I ran this command to time the command’s duration/runtime:

time ./vol_simd

Result:

Generating sample data. Scaling samples. Summing samples. Result: -574 real: 0.028s user: 0.019s sys: 0.009s The file size: 74752 bits 500000 sample size

- Real is the combination of user time and sys time together/ combined. This will be the total time that the command ran on the system.

- User is the time it takes to execute the command on the user’s side.

- Sys is the system time it takes to call/execute the command.

Test 1 Comparison:

I could do a comparison with the other sampling program given to me by professor Chris Tyler that I have tested before:

vol1.c

#include "stdlib.h"

#include "stdio.h"

#include "stdint.h"

#include "vol.h"

// Function to scale a sound sample using a volume_factor

// in the range of 0.00 to 1.00.

static inline int16_t scale_sample(int16_t sample, float volume_factor) {

return (int16_t) (volume_factor * (float) sample);

}

int main() {

// Allocate memory for large in and out arrays

int16_t* in;

int16_t* out;

in = (int16_t*) calloc(SAMPLES, sizeof(int16_t));

out = (int16_t*) calloc(SAMPLES, sizeof(int16_t));

int x;

int ttl;

// Seed the pseudo-random number generator

srand(-1);

// Fill the array with random data

for (x = 0; x < SAMPLES; x++) {

in[x] = (rand()%65536)-32768;

}

// ######################################

// This is the interesting part!

// Scale the volume of all of the samples

for (x = 0; x < SAMPLES; x++) {

out[x] = scale_sample(in[x], 0.75);

}

// ######################################

// Sum up the data

for (x = 0; x < SAMPLES; x++) {

ttl = (ttl+out[x])%1000;

}

// Print the sum

printf("Result: %d\n", ttl);

return 0;

}

vol.c and vol_simd.c programs have a huge difference in time.

The file size is gotten from the Linux command:

ls -l

vol.c had these results:

500000 sample size Result: -86 Size of file: 70808 bits real: 0.036s user: 0.027s sys: 0.009s

vol.c results had a slightly slower time by a couple of milliseconds compared to the vol_simd.c results. vol_simd.c had a larger file size than vol1.c.

(74752 bits compared to 70808 bits)

This shows the trade-off of faster time needs more file space. Less file space will cause the program to run slower.

Test 2:

What will happen if I changed the sample size in vol.h to 5000000?

I then performed these steps to still have an original copy of the program in case I break or cause a problem with the program. There were the steps:

- I copied vol.c and named it vol2.c

- I copied vol.h and renamed it to vol2.h

- I edited the vol2.h to have 5000000 instead of 500000

- I edited the Makefile to compile with the new files: vol2.c and vol2.h

Using these commands:

cp vol_simd.c vol_simd2.c cp vol.h vol2.h

Change the sample size to 5000000 using this command:

vi vol2.h Press the "i" key to insert a new '0' Press the escape key to get out of the Insert mode of Vim Editor Type ':x' to save and exit out of Vim Editor

Change this:

#define SAMPLES 500000

Into this:

#define SAMPLES 5000000

Now I will edit the Makefile using this command:

vi Makefile (Repeat the process like in vol2.h file to insert and save the changes)

It will look like this(The text in red):

BINARIES = vol_simd

CCOPTS = -g -O3

all: ${BINARIES}

vol_simd: vol_simd.c vol.h

gcc ${CCOPTS} vol_simd.c -o vol_simd

vol_simd2: vol_simd2.c vol2.h

gcc ${CCOPTS} vol_simd2.c -o vol_simd2

test: vol_simd

bash -c "time ./vol_simd"

gdb: vol_simd

gdb vol_simd

clean:

rm ${BINARIES} || true

I compiled the file and timed it using this command:

time make vol_simd2

The compile time was:

real: 0.119s user: 0.082s sys: 0.035s

File Size: 74760 bits

I then ran the program with the time command using:

time ./vol_simd2

The Results:

Generating sample data. Scaling samples. Summing samples. Result: -574 real: 0.028s user: 0.028s sys: 0.000s

I ran the program a second time to see if there was a difference to the result:

real: 0.027s user: 0.018s sys: 0.009s

Comment:

This did not change much as the file size only increased by 8 bits.

Test 3:

I thought that there must be an impact if I increased the sample size even further.

I repeated the same steps to copy and edit the new files: vol_simd3.c vol_simd3.h using the Linux copy command ‘cp’ and the Vim Editor ‘vi’ command.

I changed the sample size from 5000000 to 5000000000.

I compiled the program again.

These were the results:

File Size: 74760 bits

Compile time: real: 0.122s user: 0.062s sys: 0.056s

Then running the program with the time command and these were the results:

Generating sample data. Scaling samples. Summing samples. Result: -574 real: 0.027s user: 0.018s sys: 0.009s

Comment:

It seems to have cut off after a certain threshold and did not start to take more system resources or crash the system.

Test 4:

I thought what would happen if I reduced the sample size to see if there was an impact to the system since increasing the sample size did not change the results.

I changed the sampling size to 5000 and re-compiled the program vol_simd4.c and vol_simd4.h.

The results:

File Size: 74760 bits

Result: -574

Compile time: real: 0.116s user: 0.082s sys: 0.034s

Run time: real: 0.027s user: 0.018s sys 0.009s

Comment:

Changing the sample size did not change anything as the compile time and run time were relatively the same as the original vol_simd.c program. The file size also remained the same at 74760 bits.

Test 5:

I tested what would happen when I changed the value of 32767 to 32768 in this line of code:

vol_int = (int16_t) (0.75 * 32767.0);

The Results:

File size: 74760 bits

Compile time: real: 0.116s user: 0.091s sys: 0.025s

Generating sample data. Scaling samples. Summing samples. Result: -66 real: 0.027s user: 0.027s sys: 0.000

I ran it a second time to check if there were any changes:

Generating sample data. Scaling samples. Summing samples. Result: -66 real: 0.027s user: 0.027s sys: 0.000s

Comment:

Not much changed. The file size remains the same. The compile time and run time were relatively the same. Only the result changed from -574 to -66.

Questions left in the file vol_simd.c by Professor Chris Tyler

Q: What is an alternate approach?

A: The alternate is to allow the compiler to automatically

choose which registers to use and allow the optimization to

run based on the algorithms designed by the developers of the GNU compiler.

Q: Should we use 32767 or 32768 in next line? why?

A: We should use 32767 since we have already defined a maximum limit for the samples.

The samples are starting from the minimum value of an int16_t or a 16-bit signed

integer to the maximum value of the 16-bit signed integer.

Q: What does it mean to “duplicate” values in the next line?

Code:

__asm__ (“dup v1.8h,%w0”::”r”(vol_int)); // duplicate vol_int into v1.8h

Reference:

(dup)

Microsoft Visual Studio 2017 duplicate definition

(vector registers)

GNU vector registers

A: A duplicate is stored into a vector which will act as an

array of equal size. The value to duplicate is “%w0”

which is the 32-bit register “0”. The values to duplicate

will be sent into the “dup v1.8h” command.

The “8h” in the code is eight copies of the values to duplicate and

will store the value into the “%w0” register.

Q: What happens if we remove the following two lines? Why?

: [in]”+r”(in_cursor)

: “0”(in_cursor),[out]”r”(out_cursor)

A: This line:

: [in]”+r”(in_cursor)

This line will use the input operand as

both input and

output. Removing this will cause the while loop

to not move from the sampled position.

The line:

: “0”(in_cursor),[out]”r”(out_cursor)

The “0” indicates the in_cursor is the same

registry as register “0”(Input is using the same register as Output). The code [out]”r”(out_cursor) will be the name/ alias to the general

register “r”. Removing this line will allow/make the

compiler choose any random general

purpose register and store that data into it.

Removing these lines of code will defeat the purpose of the inline assembler code.

Inline Assembler code is for hard-coding/setting the registers with a

given value. Also, this will ensure that the registers on the system will not be randomly used by the GNU compilers. For example: Erasing data for optimization purposes.

Q: Are the results usable? Are they correct?

printf(“Result: %d\n”, ttl);

A: The answer is yes since the result did not change like the vol.c sampling program done before and changing the sample size did not change the file size since this program is well optimized.

Comment:

The program is well optimized when the file size shows little change and using SIMD and Vector registers allow a more compact area to store values into registers.

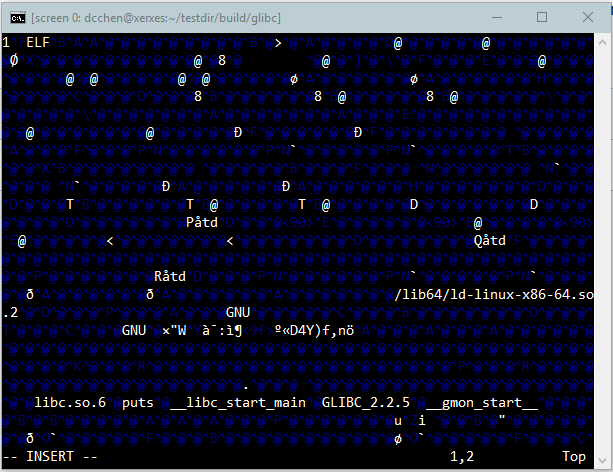

Final Task: Checking a package written by the Open-Source Community for any inline assembler code

I will be searching the libmad package. This packages is a MPEG decoder package designed for decoding video images.

I should first check if there is any installed packages

yum search [package_name]

Also, I did not know which Fedora version I was using on the school’s machine so the command allowed me to see which version of Fedora Linux I was using.

Version: Fedora 28(Aarch64)

Note: You can use this command to install the package:

sudo -c 'yum install libmad'

Instead, I will download a new source file package for testing

from the Fedora website for packages

https://apps.fedoraproject.org/packages/libmad

I will also be getting the Latest Released Version. The reason is to have the most stable version without major bugs/ problems from the developers.

libmad-0.15.1b-26.fc28.src.rpm

Site:

https://koji.fedoraproject.org/koji/fileinfo?rpmID=15431115&filename=libmad-0.15.1b.tar.gz

I will create a new directory to store the test.

mkdir -p test

The command will make a parent director called ‘test’.

I will change to that directory using this command:

cd test

I will use the following command to get a copy of the source code from the website link.

wget https://kojipkgs.fedoraproject.org//packages/libmad/0.15.1b/26.fc28/src/libmad-0.15.1b-26.fc28.src.rpm

Note: This package is in the rpm format and I will need to get the .tar.gz file from inside the rpm file to get the source code.

I then did a Google search on how to extract rpm file.

Site:

http://www.e7z.org/open-rpm.htm

The site told me to use an extraction tool called rpm2cpio

Note: If not installed, install using this command:

yum install rpm2cpio

Following the instructions for Extract files on Linux using rmp2cpio by replacing the pkgname with the actual name of the package and replacing package.rpm with my corresponding package (libmad-0.15.1b.tar.gz) from the template below:

mkdir pkgname cd pkgname rpm2cpio ../package.rpm | cpio -idmv

Now I can extract the source code in the .src file:

tar xvf pkgname

Note: Remember to replace the pkgname with the corresponding package that you are using.

I will now try to find specific files(Assembler files) in Linux using the following command:

find . -name "*.[sS]"

The only file found was imdct_l_arm.S

The difference of .s or .S type file

.S vs .s:

.S is a file sent to the C compiler and .s is compiled using the assembler directory

I then checked how many codes where actually in the imdct_l_arm.S file using this command:

grep "r[0-9]" imdct_l_arm.S | wc -l

What the command does is check any lines with the specific pattern “r” followed by any number. This indicates a register since this is an Aarch64 system assembler Code for registers. II were use a different search method on a x86_64 system. Something like this:

grep "r[a,b,c,d,x,0-9]" [filename] | wc -l

Note: filename is the filename corresponding to the x86_64 system.

There was 541 lines of assembler code handling registers in the dedicated Assembler file.

I will now check how many codes in the package that actually contain in-line assembler code.

I searched using this command:

egrep "__asm__" -R

Note: This did not return anything. Meaning there isn’t an individual file for containing the assembler code.

I tried a different pattern to check if there were any inline assembler code using this command:

egrep "asm" -R

The result shows that there are a lot of in-line assembler code in some of the files of the package.

Now to count how many code there are. Inline assembler code are separated with a newline and with the phrase “asm”. I then used this command to count each newline with a matching “asm” pattern:

egrep "asm" -R | wc -l 83

There were 83 files found. These can be found in:

- mad.h(26 lines of asm code)

- TODO (4 lines of asm code)

- fixed.h(26 lines of asm code)

- msvc++/mad.h (25 lines of asm code)

The registers for the assembler code are designed for an aarch64 type architecture.

Example:

asm ("addl %2,%0\n\t" \

The number of systems that can run this code is only limited to aarch64 systems but this also allows better optimization for the specific system with the loss of portability of the code to other systems.

I did a search for the other systems that this package can support from this website:

Site:

https://rpmfind.net/linux/rpm2html/search.php?query=libmad

This package can support: aarch64 armhfp x86_64 i386 ppc64 ppc64le s390x

A total of 7 different architecture systems

Final Comment:

The down side of optimization on a specific architecture is the number of different constraint that can be set in the assembler language. Another down side is whether the architecture supports SIMD(Single Instruction, Multiple Data – Basically one instruction performs multiple commands) and Vector registers(Special registers aside from the architecture specific registers). I can see that programs can offer optimization (Faster compile time, faster run-time/ execution time) or offer portability (Different systems and architecture) and sometimes both. Both optimization and portability are time-consuming and costly for each architecture and system.